Most people are familiar with robots via science fiction and popular culture. Most people, I'm sure, don't find the notion of a "thinking machine" all that farfetched; as one presenter at the Second Singularity Summit pointed out, humans are capable of anthropomorphizing

rocks, at least on a sentimental level. But regardless of how easy it is to

imagine human-type intelligence (or "general intelligence") in something that isn't actually human, we humans still haven't figured out how to create anything like

Data from

Star Trek: The Next Generation, or even

Hal from

2001.

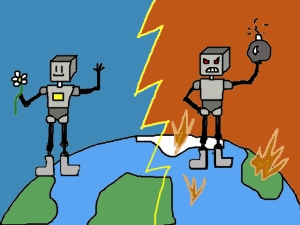

Some people see this -- the absence of artificial general intelligence (AGI) -- as an engineering challenge waiting to be addressed. Others see it as an endeavor that could lead to tremendous benefit for all (though the exact nature of this benefit is often described in terms that are nebulous at best). Still others see the prospect of powerful, autonomous AI as being a serious danger we need to attempt risk-mitigation on to the greatest extent possible

just in case it comes into being. Many have views that are a mixture of all three of these things. And I haven't even gotten into the seemingly neverending debate over whether "AGI" is even likely to be possible, and if it is possible, how (and when) it is most likely to actually come into being.

I attended the Saturday Singularity Summit session in the hopes of getting at least

some clarification regarding the controversies noted above.

Overall, the Summit was very "academic" in feel and flavor -- while far from lacking in exuberance, the speakers and audience were smart, civilized, and serious. Despite various individualized interpretations of the term, the general impression I got was that most AI-oriented people seem to use

singularity as shorthand for "the point at which (or period during which) an artificial intelligence that surpasses human intelligence in some obvious, important way is developed".

One of the analogies employed by several presenters during the

Singularity Summit was the likening of a powerful artificial intelligence to a black hole: something that creates a condition beyond which outcome-prediction becomes impossible (or at least very, very hard). The prospect of "smarter than human intelligence" is like a black hole in that we don't know precisely what would happen beyond the "event horizon" of its creation.

That, I suppose, makes sense.

However, this analogy breaks down (at least in my mind) in that black holes, unlike AI, began as theoretical objects meant to fit a particular model of the universe. In that sense, black holes are far more concrete an idea than AI is, regardless of the difficulty in knowing exactly what goes on inside them. There is no corresponding AI-shaped hole in human reality, though there certainly doesn't need to be in order for people to be compelled to create artificial intelligence. If one thing can be said with certainty about humans, it's the fact that

we like to make stuff. Moreover, we like to make

useful stuff. And in recent years, the idea that our stuff might start getting ideas of its own at some none-too-distant point has been creeping further and further into general consciousness. Hence, the Singularity Summit.

Keynote speaker

Rodney Brooks suggested in the title of his presentation that it is better, perhaps, to think in terms of "The Singularity" as a period, not an event. Brooks' spin on the "singularity" concept seemed to be that it is best described as a sort of gradual increase in the pervasiveness of certain kinds of computing resources throughout the human community. At the beginning of his talk, he emphasized two main points: that the future "needs AI and robotics" (in part due to an aging population that could benefit greatly from better, smarter technological assistance), and that simplistic attempts to speculate about an AI-infused world are bound to be inaccurate, because the world itself is far from static.

Brooks pointed out that the people who saw the first hot air balloons floating over Paris in the 18th century would have had no grounds for speculating about such things as aircraft noise and sky traffic -- therefore, any attempts we make today to expound upon the issues posed by advanced AI must not simply "overlay" technological speculations atop the familiar contemporary landscape. Doing so tends to result in laughably anachronistic science-fiction scenarios that have little bearing on reality.

Brooks also spent some time discussing the social relationships humans are beginning to develop with robots as "smart machines" become more ubiquitous and affordable. I was amused to hear that there are

sites devoted to Roomba fashion, and intrigued to learn that there are now

thousands of robots being used in military operations. Of course, these examples represent "narrow AI" of a type that is unable to learn new skills (as a "general AI" presumably would), but they still represent an interesting social test case for people's reactions to robots.

Brooks continued the "social robots" discussion by describing research specifically geared toward human-machine interactive relationships. He showed a brief video of people in a laboratory working with

Kismet, a cartoonish 'bot with fully articulated facial features. He (along with several other presenters) expressed the notion that robots "need" to be designed to respond to people in particular ways, so that people will be comfortable with them and find them comprehensible. I found this rather funny, in the sense that it almost seemed like he was saying that "social robots" need to be designed to accommodate

neurotypical humans; that is, they need to acknowledge you in particular, typical ways when you enter a room, and display particular, typical facial expressions in response to specific situations.

I'm a fair bit skeptical of this approach -- it seems almost like the same kind of thinking that led to abominations like the

Microsoft Search Puppy. But, if these robots end up being as intelligent as some people seem to think they might, perhaps they'll also be able to adapt to the communication preferences of the humans who reside with them (

protocol droids, anyone?)

Brooks wrapped up his talk by speculating on several points about the "emergence" or development of powerful AI. He sees the prospect of "accidentally emergent" AI as about as plausible as "accidentally" building a 747 in your back yard -- which is to say, somewhat less than plausible. He then invoked one of the more common "doom" scenarios -- the one in which an AI comes into existence, but thinks of humans the way we might think of chipmunks (I guess the best we can hope for in that situation is that they find us to be

cute...). He also offered a "reality check" in suggesting that perhaps humans just aren't smart enough to build an AI of the type the AGI scientists have in mind. Finally, he came back around to his earlier point about the world in which AGI emerges being a changed one -- one in which many humans have neural implants and other modifications, which of course will change the nature of the AIs we develop and our interactions with them. In short, according to Brooks, "we and our world won't be 'us' anymore."

Next,

Eliezer Yudkowsky spoke in an attempt to demystify the term "singularity" for the masses on the first day of the Summit this year -- he introduced the idea of there being "three schools of thought" with respect to the singularity concept.

These schools of thought are supposedly "logically distinct", but, according to Yudkowsky, "can support or contradict each other's core or bold claims". Personally, I find the first school of thought -- the idea of futurism being "linear" -- to be mostly absurd. Regardless of our ability to plot developments toward a particular outcome on a graph in hindsight, it isn't clear that this works in the forward direction very well. It's a lot easier to figure out how to reassemble a dinosaur skeleton from fossilized bones than it is to look back into evolutionary history and determine, at some point long before dinosaurs appeared in the biosphere, that a brontosaurus was somehow "inevitable".

The second school of thought -- the one that Yudkowsky describes as implying "a future weirder than jet packs and flying cars" -- was a fairly popular one at the Summit; understandable, since that idea fits well with the notion of advanced AI as a kind of event horizon. When you can't predict what is likely to happen beyond a certain point, you have to steady yourself for the possibility of High Weirdness beyond anything a modern sci-fi author might postulate. I see contemporary reality as

already as weird as Daliesque dreamscapes in many ways (I caught a few episodes of

Teletubbies a few years back, and haven't been the same since), so I'm not particularly

worried about weirdness so much as curious.

The third school of thought -- the one positing the idea of an "intelligence explosion" -- is probably the most compelling, in both the dramatic and in the practical sense. The critical assumption here is that, whether by circumstance or by design, something humans would recognize (or at least think of) as "intelligent" would be both (a) willing, and (b) able to optimize its own programming and perhaps even appropriate additional computational (or physical) resources in the interest of bettering itself. Whether or not an "intelligence explosion" is truly plausible is a very important question to ask -- a lot of people find the idea farfetched, or at least trivial in light of the fact that we've got world hunger, global warming, and torture to deal with, but I don't see what's wrong with at least a few people putting their heads together to mull the question over.

The reason I think the question of whether an "intelligence explosion" is plausible is worth asking is because of the nature of software. Software is extremely powerful in proportion to the physical resources it requires to run. In a sense, the "intelligence explosion" question is more properly about

power. The raw materials needed to create algorithms -- cognition, symbology, mathematics -- have been around for years.

The existence of powerful computers that manage everything from bank transactions to life-support machines has not come about due to any kind of magic, but due to basic, mundane things like hard work and chance. In short, it doesn't seem that anything really mind-bogglingly amazing would need to happen in order for a self-improving machine to come into existence.

It seems a bit short-sighted, therefore, to assume that since there aren't any obvious "harbingers" of an intelligence explosion, it is therefore ridiculous to talk about the possibility of one. There's nothing more special at the subatomic level about a microprocessor than there is about a chair, but one is inarguably more powerful than the other from the human perspective.